Introduction

Being an introverted child, I found it difficult to be with people. Later on, I found solace in technology, leading me to become an IT engineer. My perspective shifted dramatically during a school visit in central Vietnam, where our team showed how to use computers for children with disabilities. Many were victims of decades-old war remnants, including landmines and Agent Orange.

Despite their challenges, these children radiated positivity and dreams. Their gratitude for our efforts overwhelmed me, sparking a rollercoaster of emotions. I was devastated by the war’s lingering impact, yet inspired by their resilience.

That day, I realized my discomfort around people stemmed from feeling unhelpful. This epiphany led me to reconsider my path. I chose education as a means to contribute and heal alongside communities in need.

My journey to Jena and Berlin became a pilgrimage, reconnecting me with my purpose and my “why.” In this report, I will share what I learnt, whom I talked to and how I reflected on my own journey while developing a sense of what I should do in the future.

Reconciliation as a Trans-disciplinary Approach

My journey to Jena and Berlin evolved into a profound exploration of reconciliation as a trans-disciplinary approach, challenging and expanding my perspective in ways I hadn’t anticipated.

The lectures and workshop on August 19th was particularly transformative. The concepts introduced in Professor Leiner’s lectures resonated deeply with my transition from IT to education, illustrating how diverse fields can contribute to peace-building efforts.

As we delved into the 17 practices of reconciliation, each drawing from multiple disciplines, I found myself reflecting on my own potential contributions. Could my background in technology be applied to creating virtual peace networks or digital platforms for dialogue? Could my current major in education contribute to mutual understand, challenging the taboos and promote ‘living in harmony’? This realization was both exciting and humbling, showing me that my previous skills weren’t obsolete, but rather could be repurposed for this new field.

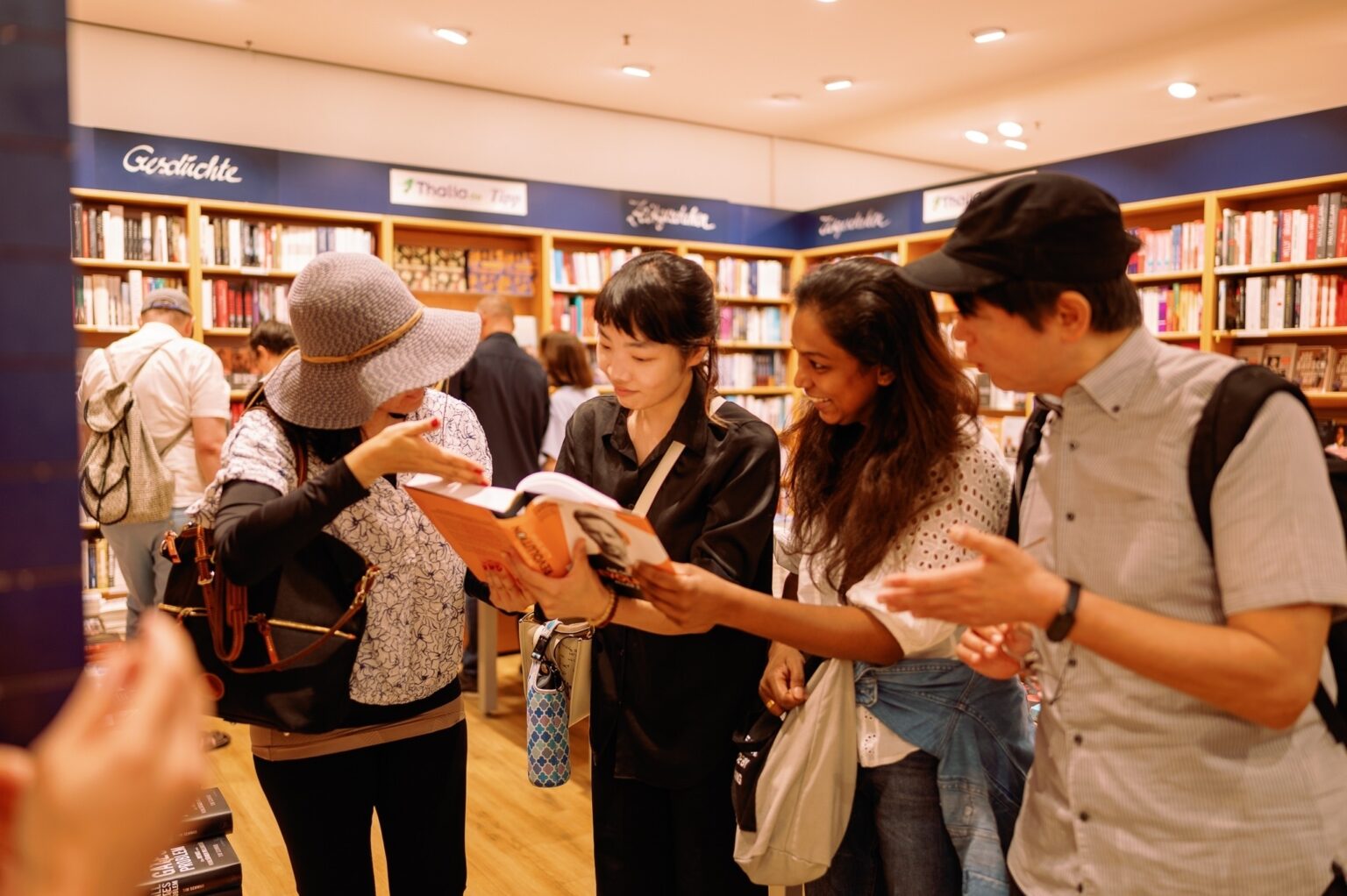

Perhaps the most impactful part of the workshop was the hands-on collaboration with scholars from various disciplines. I engaged with scholars with architecture background and international relations, experienced firsthand the power of diverse perspectives in crafting comprehensive solutions. This exercise wasn’t just about academic collaboration; it was a microcosm of reconciliation itself – bringing together different viewpoints to create something greater than the sum of its parts.

The concept of “Satoyama for Peace,” introduced later in the program, further expanded my understanding. It demonstrated how environmental education could be integrated with conflict resolution, showcasing the truly interdisciplinary nature of modern peace-building efforts. This holistic approach resonated with my own journey, reminding me that true reconciliation often begins within oneself, requiring us to unlearn and relearn.

Berlin: A Mirror of Division and Hope for Reconciliation

Our journey continued with an emotional study tour to Berlin, a city that stands as a living testament to the complexities of division and reconciliation. As we visited key historical sites, I found myself drawing unexpected parallels between Germany’s past and Vietnam’s history, deepening my understanding of the far-reaching impacts of national division.

We visited the Wannsee Conference venue, where the Nazi regime had planned the “Final Solution”, and the Topography of Terror – where we could have a glimpse into the crimes committed by the Nazi. The weight of history was intense, and I couldn’t help but reflect on how ideological extremism can lead to unimaginable brutalities. It made me think about the ideological divisions that had torn Vietnam apart, although in very different circumstances.

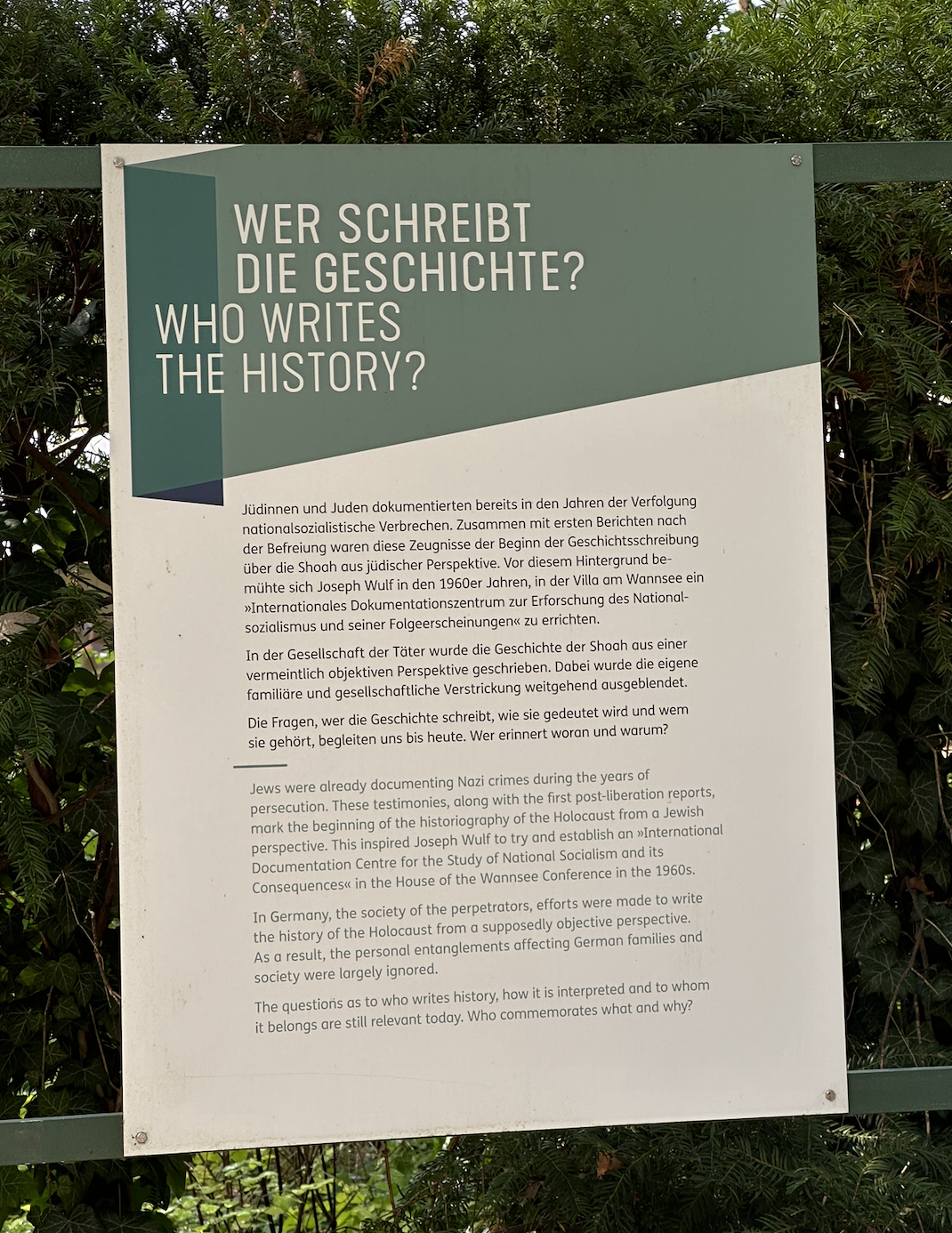

The trips to the Potsdam Conference venue, the remains of the Berlin Wall and Checkpoint Charlie served as stark reminders of how physical barriers can symbolize deep-seated political and social divides. Standing before these remnants, I was struck by the realization that while Vietnam’s division hadn’t manifested in a physical wall, the psychological and emotional barriers between North and South had been just as real and devastating. It left me with the question I read there: Who writes the history?

However, it was our visit to the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial, a former Stasi prison, that affected me most profoundly. As we toured the facility and heard accounts of surveillance, interrogation, and imprisonment, I was overwhelmed by the similarities to stories I had heard from older generations in Vietnam. The methods of control, the suppression of dissent, the separation of families – these echoed painfully familiar narratives from both war and post-war periods in Vietnam.

This visit stirred a complex mix of emotions. I felt a deep sadness for the suffering endured by people on both sides of these divided nations. Yet, I also felt a sense of hope, seeing how Germany had managed to confront its painful past and work towards reconciliation. It made me wonder about the unaddressed trauma in Vietnam’s history and the potential for healing that still lies ahead.

The Berlin experience brought into sharp focus the long-lasting effects of nation-division. It highlighted how the wounds of such divisions run deep, affecting not just the generation that experienced the split, but reverberating through subsequent generations. I realized that the work of reconciliation isn’t just about addressing visible, physical divides, but also about healing the invisible scars that persist in collective memory and national awareness.

Reflection on My Project

I would like to share the experience of presenting my project on study abroad experiences and reconciliation, which is based on collaborative autoethnography. This project aims to explore the intersections of personal experience, cultural memory, and reconciliation through the lens of study abroad programs.

During my presentation, I explained how this methodology allows for a deep dive into the personal narratives of two researchers – myself and a colleague – as we navigate our experiences before, during, and after our study abroad programs. Our focus is on how these experiences shape our understanding of reconciliation, particularly in the context of Vietnam’s relationships with Japan and the United States.

The presentation sparked engaging discussions and thought-provoking questions from the audience. One key area of interest was the construction of memory and its relationship to emotion. Colleagues were curious about how our personal memories, shaped by factors such as education and cultural background, influenced our perceptions and critical reflections during the study abroad experience.

There was also significant interest in the process of identity sense-making throughout different phases of the study abroad experience. Audience members encouraged me to delve deeper into how our identities evolved and were reconciled within ourselves and in relation to others during these distinct time periods.

Several attendees emphasized the importance of providing more historical context, particularly regarding the transformation of Vietnam’s relationships with Japan and the United States. They suggested that this broader historical perspective could enrich the analysis of our personal experiences.

Lastly, there was a call to explore the future-oriented aspects of our study. Colleagues were interested in how our experiences might shape our imaginations of future reconciliation efforts and international relations.

These insightful comments and questions have provided valuable directions for refining and expanding my research. They’ve highlighted the need to more explicitly address the emotional components of memory construction, to further contextualize our personal narratives within broader historical frameworks, and to consider the future implications of our findings. As I move forward with this project, I’m excited to incorporate these perspectives, deepening the analysis and broadening its relevance to the field of reconciliation studies.

Conclusion

As this transformative journey through Jena and Berlin came to a close, I found myself reflecting deeply on the non-linear nature of reconciliation and my own evolving path within it. My transition from an introverted IT engineer to an aspiring educational researcher and peace-builder suddenly seemed less like a departure and more like a natural evolution. Each experience – from my encounter with resilient children in Vietnam to witnessing the remnants of division in Berlin – had been a crucial step towards a more comprehensive understanding of reconciliation and my role within it.

The Berlin experience, in particular, added a profound layer to my understanding of reconciliation as a trans-disciplinary approach. It vividly demonstrated how history, politics, psychology, and education intersect in the process of healing national divides. The parallels I observed between Germany and Vietnam provided a new perspective on my own country’s journey towards reconciliation, highlighting that while contexts differ, the underlying human experiences of division, suffering, and hope for unity are strikingly similar.

However, what made this trip the most memorable is the opportunity to talk and discuss with professors and colleagues, especially experts from other disciplines. It has shown me that in the complex world of peace-building, every perspective and skill set has the potential to contribute to positive change. The trans-disciplinary nature of reconciliation studies offers a space where my diverse background is not just accepted, but is a valuable asset, opening countless opportunities for innovation in peace-building and education

Looking into the future, I feel a renewed sense of purpose and a strengthened commitment to fostering dialogue and understanding, not just between individuals, but between different parts of a nation’s fractured history. I now see the crucial importance of confronting historical truths, no matter how painful, and creating spaces for shared understanding, especially for younger generations who live with the legacy of historical traumas they didn’t directly experience.

My journey, which began with a simple desire to help others, has led me to a field where I can integrate my skills with my passion for education and social change. Armed with a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the complexities involved in healing the wounds of national division, I feel prepared and motivated to contribute to peace-building efforts in Vietnam and beyond.

This experience has reinforced my belief in the power of education and dialogue as tools for reconciliation. As I move forward, I carry with me the lessons learned from Jena and Berlin, ready to apply this transdisciplinary approach to foster understanding, heal divides, and contribute to a more peaceful world.