Philosophy and PsychologySecurity and Human RightsResearch Collaborator

Natsuki Katayama

都留文科大学 専任講師テニュア

Three main achievements

- 『ルワンダの今:ジェノサイドを語る被害者と加害者』風響社、2020年

- 「『ジャガイモをおいしくするもの』: 笑いを誘うルワンダ詩」スワヒリ&アフリカ研究 (31) 1-16、2020年

- 「スワヒリ語を話すルワンダ人」スワヒリ&アフリカ研究 (34) 70-87、2023年

詳細はURL参照 https://researchmap.jp/72ki

Field of specialization

African area studies

The kind researcher you aim to become

Thirty years have passed since Genocide in Rwanda, and it is being forgotten as an event of the past. I aim to be a researcher who continues to share accurate information regarding its history and testimonies of parties, gathered through field research and literature review.

I also aim to take a broad interest in and investigate the post-genocide situation. For example, The UK and Rwanda agreed a Migration and Economic Development Partnership in April 2022. This means that asylum seekers who come to the UK across the Straits of Dover illegally are transferred to Rwanda, and the UK provides financial assistance to Rwanda. The law was passed in April 2024 and the transfer will take place in July 2024. I am focusing on this trend.

My research theme (incorporating discussion on universal value and collective memory)

My research is the building of relationships between survivors and perpetrators after Rwandan genocide, focusing on compensations ordered by “Gacaca Courts”.

The 1994 Rwandan genocide killed at least 500,000 people in 100 days and millions became refugees. The reason for such serious damage was that many civilians were incited and involved in the crimes. It was estimated that it would take more than 100 years to try the vast number of crimes by ordinary justice, so temporary “Gacaca Courts” were enacted. These courts were set up in 12,000 locations in cities, towns, and villages across the country, where residents without judicial qualifications served as judges and 1.95 million cases (1 million suspects) were tried over a 10-year period.

In order to investigate the reality of compensations ordered to perpetrators by Gacaca Courts, I lived in several rural villages for two years and interviewed 97 people, including victims and perpetrators and judges of Gacaca Courts. In addition, I negotiated with Rwandan government to access to court records of the Gacaca Courts, which are not available to the public, to cross-check interviews with court records.

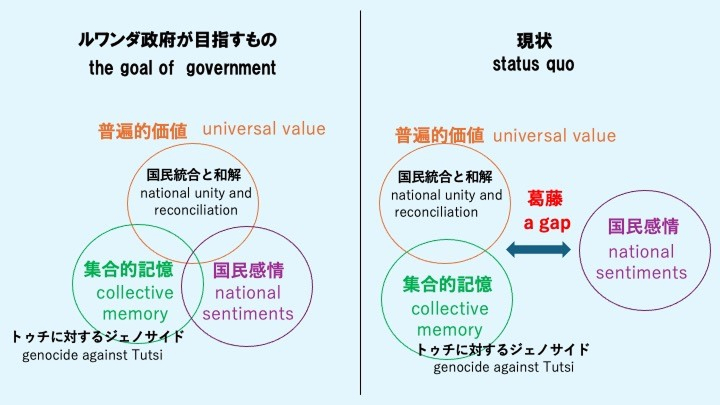

This research project aims to examine how universal value and collective memory are linked in various regions, how national sentiments grows up and takes root in society, and to systematize these cases as a study of international reconciliation.

In the case of Rwanda, the new government established after the genocide stopped writing ethnic groups on identity cards to prevent genocide that divided ethnic groups. The government has promoted the universal value of national unity and reconciliation, stating that all people are “Rwandans” regardless of ethnic groups.

The government explains “Genocide against Tutsi” as the incitement to genocide by Hutu hardliners and the massacre of Tutsi. However, Hutu and Twa who opposed the genocide were also killed, they were not officially recognized as victims according to testimonies of related parties and previous studies. In addition, war crimes committed since 1990 by the present Tutsi-centered government have been largely untried.

The government has created a storyline in which Hutu, perpetrators of genocide, apologize to Tutsi, victims, and two sides reconcile, forcing perpetrators to ask forgiveness and victims to forgive perpetrators. Gacaca courts also judged crimes according to the confession and apology of perpetrators and forgiveness of victims.

While the government unites people as “Rwandans,” it limits the official victims of genocide to the Tutsi and draws the line at the Hutu as perpetrators. This has led to a sense of “collective guilt” for being Hutu. Tutsi are also forced by the universal value of reconciliation, so they cannot express their feelings of “unforgiveness” toward perpetrators. Thus, there is a gap between national sentiments and the government’s universal value and collective memory (see the figure).

Parties of genocide remember that they have been involved with each other as residents before genocide, that they were divided into victims and perpetrators in horrific genocide, and that they will still be involved and build relationships after genocide. In this project, I will research how parties re-build and remember their relationships that were divided by genocide.

Tentative title for my upcoming working paper

How do victims and perpetrators collect memory in Rwanda genocide?

Research Image

Sunday service in a rural village