2024 Greece

A living case study: implications for reconciliation from Kavala, Xanthi, Thessaloniki and Athens

September 25, 2024

Shinshu University Center for Global Education and Collaboration Field: Comparative and International Education Assistant Professor

After a week in Germany weighing the role of place in reconciliation, the summer school in Greece added a new dimension: the power of forces that transcend place and defy borders, whether identity or values or knowledge or even music. This complicated the simplistic view of place I had developed in Germany with the site of conflict as a starting point for reconciliation. In Greece we were not at the physical site of conflict, yet the conflict was there, present in different forms.

This dimension of “invisible” forces drew my attention back to my research on global citizenship education for reconciliation. Global citizenship is placeless, promising to bind people beyond the nation or region, at least in theory. At the same time, critics of global citizenship question if anything so decontextualized can ever have to power to bind people together. Others have argued that global citizenship is not placeless as citizenship itself comes from Western thought and theory, not any universal human truth. During the summer school in Greece, I considered my experiences within these debates as I grappled with the intersections of place, values and belonging in reconciliation.

The conflict in Cyprus without Cyprus: transcending place, redefining place

The Third International Summer School in Kavala was an intensive, five-day immersion into the history, geopolitical significance and future of Cyprus and the ongoing conflict between Greece and Turkey playing out on Cypriot soil. We listened to lectures on topics spanning from the impact of Cyprus’s EU membership on the nature of the conflict to the impact of migration on Cyprus and had opportunities to speak with students from the American College of Thessaloniki (ACT) and the Aristotle University. I learned more about Cyprus in one week than I could have in months researching on my own. At the same time, we were distinctly disconnected from Cyprus. Different from the experience in Germany, in which conflict had unfolded on the very soil (or concrete) upon which we stood, we did not set foot on Cyprus, and there were no Cypriot participants present at the summer school (there was one Greek Cypriot who presented online from Cyprus). Yet at the same time, the Cyprus conflict was palpable everywhere, and not just in the sense that it was the focus of the summer school. What was binding the participants to the conflict?

The Grand Club of Kavala, the historic venue for the Third International Summer School in Kavala

Certainly, the presenters were experts on the Cyprus conflict, especially from a diplomacy and international relations standpoint. While reconciliation was not a central concern of the Cyprus presentations, several presenters touched briefly on the subject. The consensus was that the end of the Turkish occupation is necessary for the start of reconciliation, as the occupation is the root of the problem. Enforcement of international law was mentioned dozens of times as the basic prerequisite for reconciliation with Turkey. As the 1974 invasion and subsequent occupation is condemned by international society and in defiance of international law, it is up to Turkey to align with international law for reconciliation to even be considered. Indeed, one of the ACT students asked how reconciliation is possible when there is no mutual recognition, when the two countries are not even “playing the same game?”

As I listened to the discussion, I recalled the story of the prisoner at the Stasi prison in Germany. Though the former prisoner and former officer had different interpretations of the meaning of the prison and what happened there, they agreed on the reality that the prison exists and that they had both been participants in a shared past. Reflecting on that story in the context of Cyprus, I was struck by the complexity of reconciliation in a situation in which a) victims are not direct victims and b) victims and perpetrators are both separated from the physical locality of the conflict. The conflict becomes a story that is separated from the reality of the place in which it took place and the people whom it involved, allowing for multiple versions of reality constructed and performed by various actors on either side.

The treatment of Cyprus as an economically and geopolitically strategic location may perhaps be a barrier to thinking about reconciliation. As a strategic location, Cyprus ceases to be a place where lives are lived and becomes a pawn in the game of regional and international power politics. What do the people of Cyprus, Greek, Turkish or otherwise, think about the situation in Cyprus? Do they view it as a conflict? How do they approach the history? What are their lived experiences of the conflict and what realities do they function within? Do these realities match? Certainly, geopolitical realities are necessary to understand the context within which reconciliation plays out, however the Kavala summer school drove home the importance of understanding the daily realities of the people themselves.

At the same time, the conflict is not just contained to Cyprus and Cypriots. There is a larger level of conflict between Greece and Turkey that is being played out in Cyprus. Further, engagement with the EU and of international law as a basis for reconciliation involves the regional and the global in the conflict. In this sense, both EU citizenship and global citizenship are necessary for reconciliation. How does Turkey view the situation? Although not (yet) a part of the EU regional community, Turkey belongs to the global community. Could global citizenship education foster a commitment to respecting international law? Or is engagement with international law inhibiting attempts at reconciliation in this case? What role is the global community playing in the conflict and will such involvement ever supersede the level of national interest? Does it have to? Considering the potential role of global citizenship education in reconciliation of the Cyprus conflict raises interesting questions about the influence of values and belonging at both the regional and global levels.

Xanthi: a poster child for peace?

After a week of immersion in the Cyprus conflict, our colleagues from Xanthi treated us to a tour of their city, a diverse municipality in the Thrace region of northern Greece. With a complex history of occupation by the Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria and later Germany, as well as migrations over centuries of Muslim populations from Asia Minor, Xanthi is diverse in terms of religion and ethnic background. Public schools are taught in Greek, but mandatory religion classes are provided separately for Greek Orthodox and Muslim students. When I asked our colleagues if religious differences ever cause conflict in Xanthi, they were emphatic that people live together, integrated, in harmony and without judgment of each other. Certainly, Xanthi appears to be a peaceful place, a model diverse society in which people of different religious and ethnic backgrounds are integrated and living amongst each other without conflict. How was this mixed community able to maintain a peaceful society? A poster pointed out to me by a colleague during our tour of the city provided a sliver of insight.

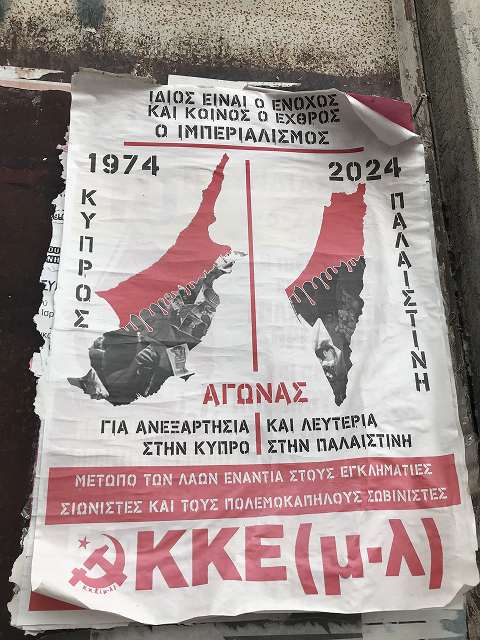

A Greek Communist Party (KKE) poster that states: “FIGHT for independence in Cyprus and Freedom in Palestine” (Google Translate)

This Greek Communist Party (KKE) poster draws parallels between the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the present conflict in Gaza, represented in the poster as the ongoing seizure of Palestinian land by Israel. A crude translation courtesy of Google Translate reads “FIGHT for independence in Cyprus and Freedom in Palestine.” A closer reading of the KKE platform found that it supports the end of the Turkish occupation, which it views as a form of imperial oppression, and advocates for a united Cyprus independent from foreign influence and decoupled from the EU. While I don’t pretend to be well-versed in Greek politics, the poster interested me as the Cyprus issue appears to bridge the political spectrum. In other words, perhaps the Turkish invasion of Cyprus and ongoing conflict creates a convenient “other” that strengthens Greek national identity and solidarity amongst political parties. Although Xanthi is religiously and ethnically diverse, at least from our conversations with our colleagues, residents identify as Greek. In the context of the local, perhaps Greek national identity serves as the glue that holds diverse communities such as Xanthi together. Is this national identity a barrier to reconciliation between Greece and Turkey? If so, will supranational identities facilitate reconciliation? Will supranational identities weaken national identities and destabilize diverse communities domestically?

Global citizenship education as decentering?

On 9/2, I presented a work in progress at the American College of Thessaloniki (ACT) titled Global Citizenship Education for Reconciliation in East Asia: Possibilities and Challenges. The presentation introduced the concept of global citizenship and how global citizenship education can facilitate reconciliation through transformative pedagogy. I then presented potential barriers for global citizenship education (GCE) to positively influence reconciliation, including GCE as an empty term, as reinforcing hegemonic power structures and a gap between theory and practice.

Umemori-sensei put a finger on a recurring dilemma I have faced in my conceptualization of global citizenship in East Asia. Why global, and not regional citizenship? Why skip “Asia”? I agree that Asia is necessary for reconciliation in East Asia. At the same time, I wonder, given the current stalemate, if a different, a wider worldview needs to be established before tackling a joint construction of Asia. Given the current tensions and the history of Asia as a Western conception, it is hard to imagine how such a construction would advance. If the focus was first on a humanity beyond Asia, would this allow for a baseline agreement from which reconciliation, including a joint construction of Asia, would be possible? The current situation with Cyprus and the EU may provide some hints. Can European values and belonging facilitate reconciliation as a starting point between Greece and Turkey when Turkey is not yet a member of the EU? At the same time, is reliance on international law echoing the concerns of critical GCE scholars who see GCE as reinforcing hegemonic power structures? Indeed, in Asia, the term global citizenship itself has been politicized, promoted heavily by South Korea while barely mentioned in Japan and China.

Asano-sensei brought place back into the discussion by suggesting that the “dark side” of education, in this case state-controlled basic education aiming to mold national citizens, should be examined as the context in which attempts at global citizenship are made. This resonated with me as I remembered Asano-sensei’s earlier comment during the 8/29 closing panel discussing nation as the center of justice, emotion and memory. At the time I wondered if global citizenship education can be, or should be, or is a force for decentering the nation as the gatekeeper of these three axes of reconciliation. Certainly, to answer this question, I will first need to establish how nations attempt to control these axes through education systems.

At the summer school in Germany I considered how place, specifically the site of conflict, may be used as a tool for initiating reconciliation of past conflict. In Greece, through the lens of global citizenship, I considered how values and belonging that transcend place may prohibit or enable reconciliation in active conflict. Both are potentially powerful lenses through which conceptualization of international education for reconciliation can be approached.